Backgrounder

A deeper dive on the Fashion Act.

-

-

-

What is a Science Based Target?

How do the Fashion Act climate targets differ from Science Based Targets?

If companies are already voluntarily signing up for SBTs, why is the Fashion Act necessary?

What is the connection between Higg and Science Based Targets?

What is the connection between the Fashion Act and the recent SEC proposal?

-

-

Why is the Fashion Act needed now?

1. Our global system is currently lawless

When global markets were stitched together in the 1970s and 1980s, the labor and environmental gains achieved in the U.S., as incomplete as they were, were not extended to global trade. Fashion companies have flooded into global markets chasing cheaper costs without the attending governance to ensure that this global trade was not exploitative, to people or the environment.

The current challenge lies in holding corporations accountable for their involvement in human and environmental abuses and providing remedy to victims. This predicament exists for two reasons:

International law does not exist. There are no binding and effective global accountability mechanisms and;

Countries, mostly in the Global South, where production has moved are reluctant to sufficiently regulate these corporations’ social and environmental conduct.

There is no regulatory entity at the global level to oversee corporate global operations and hold corporations accountable for their alleged complicity in human rights or environmental violations. Attempts at regulation introduced to date are entirely voluntary. There are “soft-law” initiatives developed by the UN including the UN Global Compact and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. While soft-law regulations might raise awareness, encourage corporations to behave more responsibly, or have an impact on corporate governance, soft-law initiatives have not curbed abuses because they rely on the voluntary participation of corporations, are non-binding, and lack monitoring and enforcement.

At the same time, governments in the Global South are reluctant to hold global fashion corporations accountable for their complicity in labor and environmental abuses for several reasons, including:

The dependence of host states on foreign direct investment leads to a lack of political will to enforce even existing laws and regulations. In the context of the fashion industry, countries are competing to get the business of brands, so they are disincentivised from developing or enforcing laws that would cause brands to flee, and;

Underdeveloped legal systems and institutions (eg no legal aid for victims or lack of resources for investigations);

Vulnerable and weak governments.

All of this leaves the victims of fashion’s environmental and labor violations without the possibility for redress in nations where fashion production takes place. Given this context, it is totally unrealistic to expect transnational corporate accountability to come exclusively from the places where fashion production actually occurs.

2. Victims in our global supply chain do not have access to justice.

Given the limitations of accountability mechanisms, the focus today is shifting to corporate home country strategies with extraterritorial effect. One of the principal strategies available to try to make global companies accountable for abuses in their supply chain is through extraterritorial jurisdiction - when a state regulates or when a court adjudicates conduct occurring outside of its territory.

In the US, global victims have tried to pursue lawsuits in US courts through a federal law called the Alien Tort Statute that gives federal courts jurisdiction over lawsuits filed by non-US residents for abuses (called torts) committed in violation of international law (such as international human rights law). It was first introduced in 1789, making it one of the oldest federal laws still in effect in the US.

But, and this is a huge but, since the 1980s, more than 120 foreign direct liability cases have been filed worldwide in the US against US-based multinational corporations for their alleged complicity in human rights abuses, but no corporation has been found guilty to date. Further, most human rights litigation cases have been dismissed.

The Supreme Court, by interpreting the law narrowly, has essentially put the kibosh on the potential power of the Alien Tort Statute.

The federal government is in political roadblock, unwilling to pass critical laws for the full functioning of our society. But the federal system is not our only way to drive regulation. Progressive states must correct this failure and pass laws that fill in this regulatory gap.

We need regulators to step up to the plate. Regulatory failure – a lack of laws – has been a driving force behind corporate short-termism and a lack of consideration for environmental, social and human rights interests. This is the heart of the failure of neoliberalism, corporations have grown focused on short term growth, while governments have not played their role of balancing that growth with the risks for broader society.

We need regulators to ensure products that are sold in US markets are not exploiting land and labor. And alongside this, we need to provide a path for those harmed by a fashion company’s negligence, to be able to seek justice.

California has done this, for example by setting state mandated fuel efficiency standards, with enormous success. These state-based fuel efficiency standards have had the effect of revolutionizing the auto industry over the last two decades, improving environmental standards while ushering in new billion dollar companies and shifting existing companies to compete not on things like speed or size but on how environmentally friendly they can make their vehicles. Regulation can create a virtuous cycle of consistently improving environmental and social standards, rather than a race to the bottom through exploitative practices.

This is what the Fashion Act does. Fundamentally, the Fashion Act ensures a fair correlation between the economic power of multinationals and their legal responsibility.

3. We are living in a climate crisis and the fashion industry is a significant contributor to that crisis

Unprecedented heat waves, wildfires, drought, hurricanes and flooding are the first wave of the climate crisis and it will only continue to get worse, unless urgent action is taken now. The fashion industry contributes significantly to climate causing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, anywhere between 4-8% of total global emissions⁵. Even with the lower estimate, that is more than France, Germany, and the United Kingdom combined. Left unchecked, this figure is set only to increase, accounting for more than 25% of the world’s global carbon budget by 2050⁶. If we do nothing, the growing GHG emissions of the global fashion industry will cancel out any gains society might make in other spaces of GHG reduction, such as in state reductions.

4. Given market dynamics, voluntary efforts have failed and will continue to do so

From the 1970’s when economist Milton Friedman was quoted as saying, “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits,” to today, corporate focus has been on short-term profit maximization.

While this dynamic has been at play, a competing trend has also made its way through the corporate world, including in the fashion sector: corporate sustainability. As the Cold War came to an end, leading western economies perceived a clear globalizing mission to use their peace, prosperity, and wealth to address shared global problems. For some, corporate sustainability was seen as an opportunity to rewrite the contract between society and capital.

But in the battle between short-term profit maximization and corporate sustainability, short-term profit maximization has won out.

In having to defend its mere existence, corporate sustainability has re-marketed itself as a business optimization function - an area that helps processes be more efficient, improve trust with consumers and regulators, and help to manage risk.

Given this context, today “corporate sustainability” is pursued only to the extent that the company can market it to consumers and financiers as a competitive advantage, thus yielding more short term profit, or because it is a legal obligation.

With these dynamics in place, it is clear both why corporations join voluntary initiatives – it's a marketing tool to win over customers and increase profits – as well as the internal dynamics that lead them to come up short when we move beyond goal setting to implementation.

Specific interest in sustainability initiatives within the fashion industry over the last ten years have not resulted in measurable progress, in fact indicators have only become work. In that time, Rana Plaza killed 1,132 people, microplastics from fashion are now in our bloodstream, and climate emissions continue to mount.

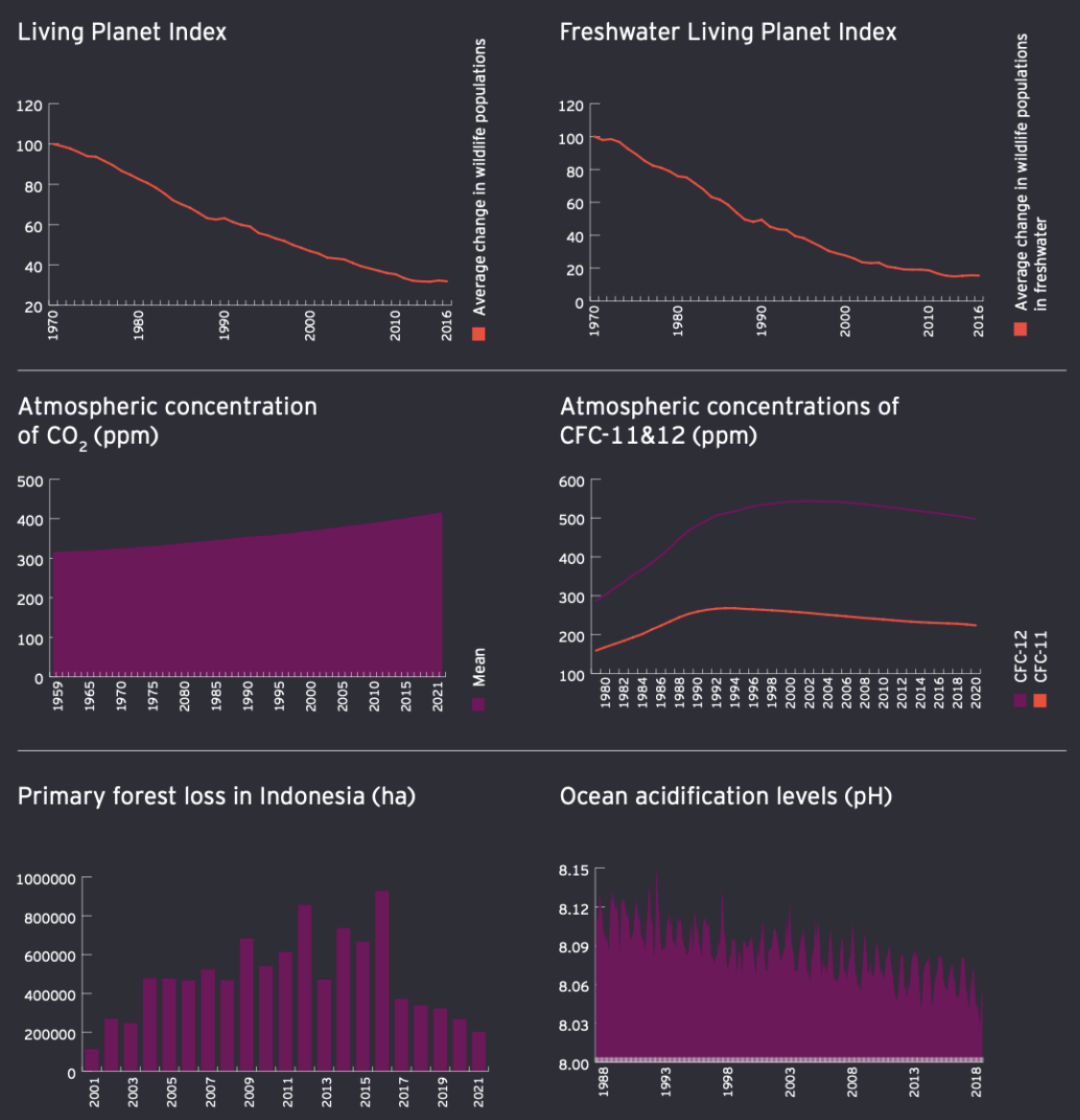

It is no surprise then, that while company involvement in corporate sustainability initiatives have increased significantly (see below), they have not demonstrated that they are addressing the defining environmental and social crises of our time.

Company involvement in corporate sustainability initiatives. ⁸

Indicators of the health of the biosphere

The job of legislators is to develop considered rules to allow society to thrive. Given that the corporate fashion world will not be achieving gains on their own, legislators must legislate to provide the basic rules to allow fashion companies to thrive within human rights and planetary boundaries.

Mandatory Due Diligence and Labor Protections in the Fashion Act

As described above, labor and environmental abuses are prevalent through the supply chain of the apparel industry. The concept of Mandatory Due Diligence was first developed by the United Nations to address these issues and achieve better outcomes for people and the planet.

Mandatory Due Diligence is the process companies are required to perform to: embed responsible business conduct into policies and management systems, identify, cease, prevent, mitigate, account for, and remediate actual and potential adverse impacts to human rights and the environment in their own operations and in their supply chains.

Within the UN, Mandatory Due Diligence has been a voluntary framework, which has led to limited results. The Fashion Act moves this voluntary framework to a legally required duty, which will, for the first time, prevent companies from evading their responsibilities towards workers and the planet. It will further provide workers a legal framework for redress.

The Fashion Act has developed the most robust version of mandatory due diligence. It combines sufficiency requirements with robust monitoring and enforcement mechanisms —both administrative and through joint and several liability— which all together turns mandatory due diligence into a dynamic means for companies to be held accountable for the impacts in their supply chains. This considered approach ensures that compliance moves away from a “tick-box” approach to ensuring a focus on actual outcomes for people and the planet.

The Fashion Act’s Mandatory Due Diligence framework contains the following key elements:

I. Mandatory Due Diligence across supply chain and for all categories of harm

Some legislative efforts applying mandatory due diligence are limited to one part of the supply chain, such as garment work, or limit due diligence requirements to one category of harms, such as forced labor. The Fashion Act, by contrast, covers all areas of the supply chain and all areas of impact - from forced labor, to deforestation. What areas the companies will be required to focus on will depend on their areas of greatest impact.

II. Requirement to act, not just to disclose plan

Mandatory Due Diligence could be put into law simply as a disclosure requirement, meaning that a company would only have to disclose how they are performing due diligence, without an accompanying responsibility to actually do anything. The Fashion Act, by contrast, mandates substantive due diligence, requiring companies to effectively carry out due diligence, which includes the requirement to effectively identify, cease, prevent, mitigate, account for, and remediate actual and potential adverse impacts to human rights and the environment in their own operations and in their supply chains. When abuses do occur, companies under the Fashion Act are required to mitigate and remedy the resulting adverse impacts.

III. Sufficient enforcement and liability

Attorney General’s Power to Investigate

Under the Fashion Act, the Attorney General is given monitoring, investigative, and enforcement powers to ensure that companies subject to the act comply with the new duty.

Attorney General’s Power to Enforce

Companies under the Fashion Act are held liable for failing to comply with their due diligence obligations. Liability under the Fashion Act arises:

For the failure to conduct due diligence;

For the failure to conduct due diligence in an effective manner

The Attorney General can fine the company up to 2% of global revenue for their failures to perform.

Joint and Several Liability for Garment Workers

Under the Fashion Act, regardless of a company’s conduct in carrying out due diligence, garment workers will have joint and several liability for any lost wages.

Joint and several liability doctrine - When two or more parties are jointly and severally liable for a tortious act, each party is made independently liable for the full extent of the injuries stemming from the tortious act.

For example, New York State recently passed S2766 which makes contractors in the construction industry jointly and severally liable for wages owed to employees of its subcontractors.

IV. Clear guidance for industry

Given that “effective” due diligence is required, the Fashion Act requires the New York Department of State to develop, in consultation with the New York Department of Environmental Conservation and the Department of Labor, clear rules and educational materials for companies to have the clearest ongoing understanding of how effective will be interpreted and provide guidance on time sensitive issues, emerging issues, and high-risk country situations. The Department is further required to assist companies to improve the quality of their due diligence processes. In this way, companies will have sufficient guidance and support to ensure that they can continue to be in compliance with the Fashion Act as situations continue to evolve.

For more information on mandatory due diligence as applied to the fashion industry, see: OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chain in the Garment and Footwear Sector.

Climate Protections in the Fashion Act

As part of the Mandatory Due Diligence framework, The Fashion Act requires companies to reduce their climate emissions in their own company and, critically, in their supply chains to levels that align with the Paris Agreement. The Fashion Act utilizes the methodology of the Science Based Targets initiative to set these targets with some modifications, described below.

What is a Science Based Target?

Science Based Targets (SBTs) are five to ten year targets that set the pace that companies have to reduce their emissions to align with the goals of the Paris Agreement limiting global warming to well below 2C above pre-industrial levels and making efforts to limit warming to 1.5C.

The Science Based Target initiative (SBTi) is a partnership between CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project), the United Nations Global Compact, World Resources Institute and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

SBTs are the de facto global standard for carbon management. Over 3,000 businesses have committed to Science Based Targets. It allows companies to move from doing something, to doing enough aligned with what science says is needed. Using science-based standards moves industry from storytelling competitions to a common definition of ambition. The SBT translates complex science into real-world corporate climate targets.

Science Based Targets break down emissions inside a company and within their supply chains into three scopes.

Scope 1: Direct GHG emissions occur from sources that are owned or controlled by the company. For fashion companies this includes the emissions from their own facilities (offices, warehouses etc), any owned vehicles and any production facilities that they own.

Scope 2: Indirect greenhouse gas emissions from consumption of purchased electricity, heat or steam. These are emissions from the generation of purchased or acquired electricity, steam, heating, or cooling consumed by the company to run its facilities.

Scope 3: Other indirect emissions, such as the extraction and production of purchased materials and fuels, transport-related activities in vehicles not owned or controlled by the reporting entity, electricity-related activities not covered in Scope 2, outsourced activities, waste disposal, etc. For fashion companies, Scope 3 is by far the most significant area of emissions, as this is the scope that includes the emissions from the supply chain, where the vast amount of emissions occur. The climate hotspot in the fashion industry is at the textile mills where clothing fibers are spun, woven, knit, dyed and finished into textiles. See C&A emissions below as one illustration.

SBT sets a minimum ambition in the short term of aligning with 1.5C for scope 1 and 2 and well-below 2C for scope 3 targets, within a time frame of 5 to 10 years. Companies cannot use offsets/carbon credits to meet targets.

For more, see: Science Based Targets initiative, Target Validation Protocol for Near Term Targets.

How do the Fashion Act climate targets differ from Science Based Targets?

The Fashion Act requires companies, at a minimum, to set and achieve Science Based Targets.

The Science Based Targets initiative currently accepts Economic Intensity Methodology for scope three emissions. The Fashion Act only allows this method for companies with revenue below $1 billion. Once companies have reached $1billion and above they will be required to reduce emissions using the absolute reduction method.

Further, the bill states that Science Based Targets are a minimum requirement, this gives regulators space to build on this, should SBT prove to be insufficient.

If companies are already voluntarily signing up for SBTs, why is the Fashion Act necessary?

While the SBTi has developed and continues to evolve a useful framework, the SBTi has no ability to legally enforce the requirement that companies actually achieve those targets. As a result, while companies that have set SBTs have shown to perform better on carbon reductions than their peers, they have NOT demonstrated that they are actually on a path to achieving the emission reduction targets. Moreover, and relatedly, it is only a few leading companies that have so far set or committed to set these emission reduction targets.

Given that carbon impacts in the apparel and footwear industries are largely within the supply chain of brands where facilities – such as textile mills – are shared by multiple brands, companies voluntarily working towards achieving Science Based Targets are put at a competitive disadvantage by carrying the cost that other companies then benefit from. This context inhibits players from both voluntarily signing up for Science Based Targets and from achieving those targets even when they do sign up for them.

Based on the broader short term profit maximization framework fashion companies operate in and the reality that fashion companies share common facilities, it is most likely that even those few companies that have voluntarily set Science Based Targets will not achieve them, unless this requirement is put into law.

What is the connection between Higg and Science Based Targets?

Science Based Targets initiative does not explicitly endorse Higg. The Science Based Targets initiative released a guidance document, Apparel and Footwear Sector: Science-Based Targets Guidance and on one page of that they have a case study on how companies could use the Higg suite of tools to set SBTs and track progress.

What is the connection between the Fashion Act and the recent SEC proposal?

In March 2022 the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed a rule that would impose mandatory climate risks and greenhouse-gas emissions disclosure requirements on publicly traded companies. There was a 90 day comment period which ended June 2022. Companies’ disclosures would require independent assurance, a type of review that’s usually performed by engineering, consulting or audit firms. Businesses also would have to review the impact of climate risks stemming from extreme weather events, such as floods, on their finances. The SEC is now in a period of considering the feedback it has received and deciding whether to amend the proposal and vote on a final rule.

The SEC has said it expects additional costs related to the proposal of $420,000 a year on average for a publicly listed small company and $530,000 a year for a bigger firm.

One of the critiques coming from industry is that the proposal would essentially require businesses to maintain two separate sets of records on greenhouse-gas emissions, one for the SEC protocol and one for the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (as used by Science Based Targets) requiring more resources and resulting in higher costs. (see WSJ piece and GAP’s formal feedback letter).

We do not know whether the SEC will amend its rule to align with the Greenhouse Gas Protocol. But the benefit of the Fashion Act is that it already aligns with the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, as that is the protocol used by Science Based Targets.

Water Protections and Chemical Management in the Fashion Act

The fashion industry is a significant user and abuser of chemicals throughout its supply chain and, in particular, in textile mills where fibers are dyed and finished and made into textiles. Poor chemical stewardship in global fashion production results in toxic waste in waterways, poor health for textile workers and surrounding communities, and negative consequences for those purchasing and wearing clothing. This chemical mismanagement is leading to both polluted and dead rivers in the sites where textile mills are located.

The Fashion Act tackles chemical management at the mill, by requiring that fashion companies work with their significant mill suppliers to implement, at a minimum, Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals’ (ZDHC’s) most up to date Wastewater Guidelines.

Additional Frequently Asked Questions

Why is this a state bill not a federal bill?

With the federal government as divided as ever, we need progressive states to step up to the plate. There is a history of states doing this with great success, such as California’s fuel efficiency standard. New York can demonstrate that, like California, it can step up with critical progressive wins.

Which companies are reached by the Fashion Act?

The Fashion Act reaches large fashion brands selling in New York State. The Fashion Act applies to fashion and footwear brands that have a global revenue of over $100 million, this includes private label brands of multi-brand retailers, if those brands together reach the $100 million threshold. (This would include, for example, the apparel and footwear private labels of companies like Amazon).

It is the largest fashion companies that have by far the largest impact, earn the most profit and have the capacity and resources to do the work required by the law. It is the top 20 fashion companies that account for 97% of economic profit. ⁹

Where is the Fashion Act in the legislative process?

The Fashion Act is a massively significant bill that, when passed, will make New York State a national and global leader in not only addressing the negative impacts of the $2.5 trillion fashion industry, but will serve as model legislation for other industries with long, global supply chains.

The bill was introduced in the 2021-2022 legislative session by New York State Senator Alessandra Biaggi and Assemblymember Dr. Anna Kelles. The bill has been assigned to the Consumer Protection Committees in both the Senate and the Assembly. Given the bill’s significance and recognizing that this is a new space for policy, the sponsoring legislators wanted to ensure that they took the time to be open to any feedback from the bill from all stakeholders interested in providing their feedback and work in dialogue with any and all stakeholders who cared to have their voices heard.

Having received this input, the legislators will release an amended bill in the 2022-2023 legislative session. In order to get the bill into law, the chairs of the Consumer Protection Committees in both houses must put it on their committee agendas where it must pass to move to each house’s floor for debate. It must then get passed in each chamber, the Assembly and the Senate. Then, to become law, the Governor must also sign the bill.

To get a bill of such significance passed requires a massive team effort, this includes you! To join the effort, head to thefashionact.org. To learn more about the legislative process we also recommend reading, Short Circuiting Policy: Interest Groups and the Battle Over Clean Energy and Climate Policy in the American States. Found here. To be an effective advocate, one needs to understand not just the outcomes hoped, but the political process that will get there.

Is there a new bill sponsor in the Senate?

Because Senator Biaggi is leaving the Senate at the end of December 2022, there will be a new sponsor of the legislation next year. We are excited about our new senate sponsor and look forward to making an official announcement in 2023, once the bill transfer is approved by Senate Leadership.